CAD - Computer Aided Design - is a near-ubiquitous digital design and modeling platform used in everything from architecture to woodworking. Most products manufactured these days first start as CAD drawings in some form or another. These can be as simple as 2D designs or as complex as hyper-realistic 3D models, complete with animation.

There are dozens of CAD software packages available, ranging from bare-bones freeware to memory-intensive behemoths used by large-scale manufacturers and the aerospace industry. Most of these programs are in part vector-based, similar to illustration programs like Adobe Illustrator or Inkscape. But CAD is not just a fancy picture-drawing platform. Many CAD packages have advanced 3D surface modeling capabilities plus virtual strength and dynamic analysis tools. CAD is effectively a digital way of representing real-world objects, complete with material specs and characteristics.

While I've tinkered with CAD in the past and often use vector-based drawing programs in my work now, I have not done any serious modeling using it for my maker projects. But increasingly, I am expanding how I make things, and I want to get more into CNC machining and possibly 3D printing. So I've decided it's high time to learn CAD for real.

A deep-dive into CAD is not necessary to start 3D printing or CNC machining at home - there are other more user-friendly software options for these tasks. But I love learning new things "just because" and prefer to crack open black boxes whenever possible. Plus, I have an immediate real-world need to make a bonified dimensional drawing for a contract build, and CAD is the modern way to do this. Plus, I'll save a ton of dough if I have the complete 3D design ready to submit to a shop.

The project involves creating aluminum control panels for AC power sources I make for conservation research (I've written about the builds here). I've entirely made the first few by hand, but it's onerous work. The panels each have thirty holes of varying sizes and dimensions, several of which have very tight tolerances (the spacing must be exact, or the parts won't fit).

I have to first transfer the design onto a sheet of 1 mm aluminum and then drill or cut each hole using the various tools at my disposal. It takes nearly a day to complete, and there are many steps along the way where I could screw it up.

Imagine getting down to the last few holes and making a mistake. Well, I don't have to imagine as I did it once (ouch).

After doing a bit of good-ol' cost-benefit analysis, I decided this is a perfect opportunity for a CAD-based application. Here, where the project is designed on the computer and then used to command a machine to do the work, it will save time. And the result will be not only expedited but also far more exact. In this case, the best way to create the part is using modern laser cutters that are computer controlled.

I then shopped around locally for a machine shop that could do the work, plus I determined what CAD file outputs the shops would need (principally a dimensional drawing, a.k.a, old-school blueprints, and a CAD file of some such file type for the machines). I also needed to decide on a software package.

Like most advanced software out there, CAD programs can be costly. And I mean very costly. Name-brand packages like AutoCAD run over $1800/year for a subscription. And more accessible programs (for non-engineers) like SketchUp can still set you back six-digit sums annually. Luckily for the frugal freelancer (that's a catchy name; I'll have to remember it), several open source options are surprisingly good.

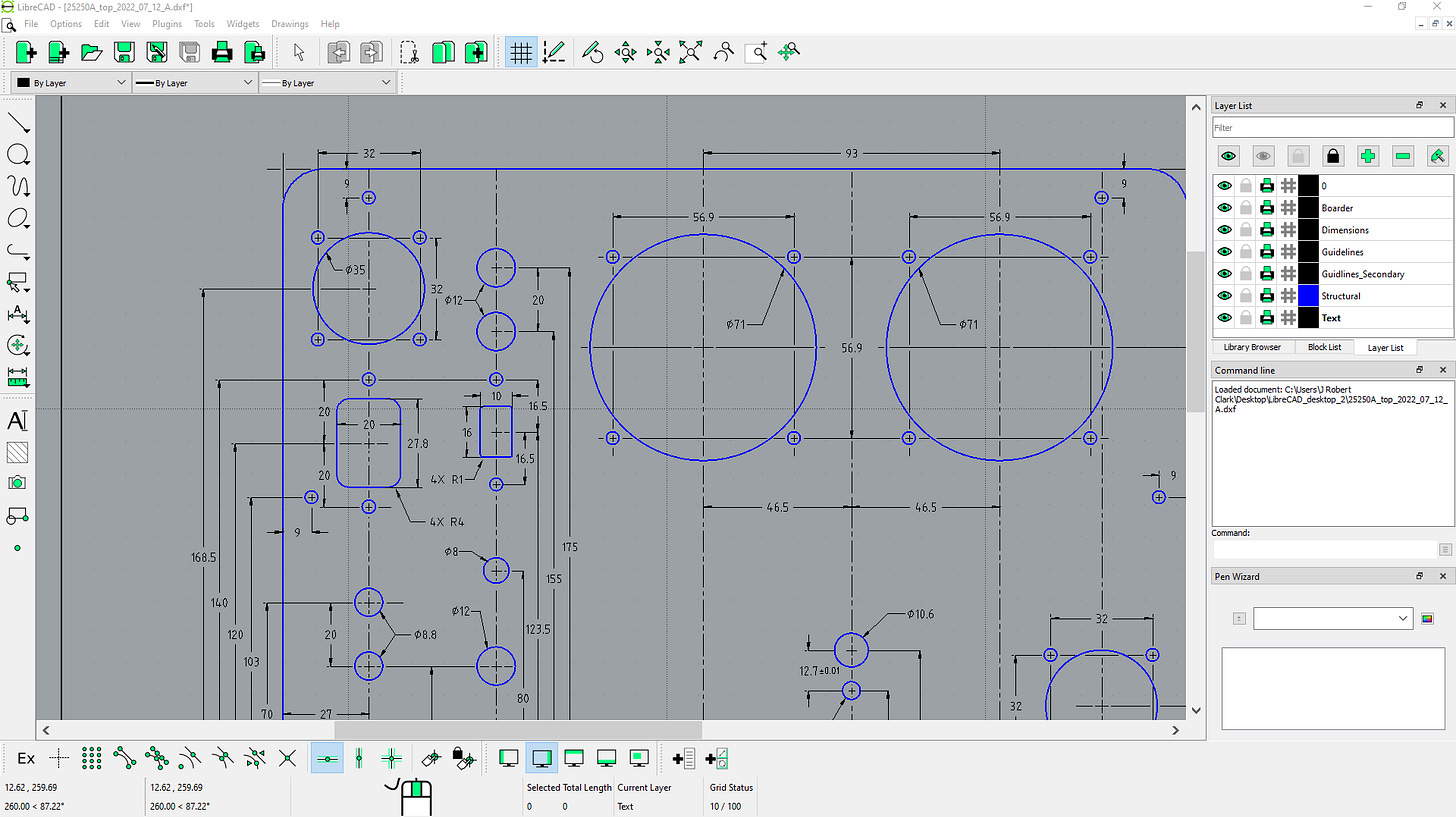

I've been learning LibreCAD and FreeCAD; as the names indicate, these are free, open-source software packages. LibreCAD is strictly 2D, vector-based, while FreeCAD is more similar to AutoCAD in having both vector and 3D rendering capabilities. But of the two, LibreCAD is most similar to other vector-based programs I've used, so I started here intending to make the dimensional drawing first.

When I say "similar," I use the word loosely. LibreCAD has a pretty steep learning curve, owing to the specific key-stroke and mouse input requirements and the nuances of how and when to execute a particular step. I suspect users accustomed to other CAD programs would feel more at home out of the gate. But for me, it took some time.

Luckily, online resources, videos, and forums provide basic tutorials and address common user questions, even for newbies. So with a little bit of internet sleuthing and video-watching, I got going with LibreCAD in a few hours. And I completed my first drawing in just a couple of days.

I wanted to make this thing 3D, of course, so I next cracked open FreeCAD expecting things to go more smoothly (now that I was such an "experienced" CAD user). Not so. FreeCAD and LibreCAD are remarkably different, and I felt like I was starting from the ground up. And that's just what I did - again, I watched several videos and read a lot of forum advice as I fumbled my way around the new-to-me software.

After considerable effort, I learned how to import my work from LibreCAD and used this to transform the 2D object into a 3D rendering. Oddly enough, the file I imported was not completely translated, so I had to do a lot of repair and tweaking. But it took far less than would be needed from scratch. Anyway, the FreeCAD file could then be saved in a format suitable for laser cutting. And I was ready to send it off to the shop.

Laser cutting isn't cheap; usually, there's a relatively high minimum cost for projects. So having a one-off prototype made is not cost-effective for me. Even if demand increases for my control boxes, I won't be making ten in a year. So 200 bucks or more to see if my design is correct is a tough sell (and possibly bad business).

While I mostly trust my CAD drawings, I want to see an actual prototype before committing to making several of them. In metal, this isn't worth it, as described. But my favorite local plastics shop can make me a prototype in acrylic for much cheaper (it's easier to laser-cut plastic than aluminum). So they're making the part this week for me. (Thanks, Scott and Martin, at MGM Plastics!)

I'll share pics of the panels once I have them made. (Maybe I'll do a side-by-side between the laser-cut and handmade.) As for this process - farming out part of a build - I had mixed feelings initially, but these are quickly transitioning into nothing but positive. Yes, I'm an ardent DIYer, so it feels a little like handing over work for someone else to do. But then I think about what it took to design the part in CAD (a lot); I did the hard job creating the design, even if it was all on the computer. So using another shop's capabilities to do the final cut-out feels relatively minimal. Besides, I couldn’t fit a laser cutter in my shop. Look at this thing:

Making is about doing a job in the best way possible; in this case, laser-cutting makes the most sense.

As for the software, if you are considering jumping in and learning CAD too, I'd suggest starting with an open source version. The only investment is time. And as far as which one, I’d go with FreeCAD. Everything I did in LibreCAD is possible in FreeCAD, plus much more. And given that either will set you back a few days' work, going with the one with more capabilities will make the investment worth that much more.

Until next time.

JRC