Happy Friday, all. In today’s post, I share a few thoughts on Right to Repair - the movement to put fixing our stuff back in the hands of consumers. I love a repair challenge, so when my aging GPS watch began to fail, I decided to give fixing it a shot. This DIY highlights both the challenges and rewards in repairing our own stuff, even when major corporations thwart such efforts. It’s often worth it and good for the planet too. So I hope you exercise your rights as I have. Together, we can make a difference. ~JRC

Way back in the second decade of the Twenty-first Century (a.k.a., 2014), I was an avid runner, logging tens of miles each week. I was training for an ultra-marathon then, and I decided to invest in a GPS watch to track my progress. I opted for a Garmin Forerunner 15 as it was relatively affordable (two hundred bucks with a heart rate monitor) and had the basic features I wanted. Alas, that ultra never happened; I sustained a life-changing lower back injury and haven't been able to run for long distances ever since. But unlike my back that crapped out on me then, my Garmin watch has kept ticking and ticking (technically beeping and beeping, since it's all electronic).

Today, I wear it as my daily timepiece and use its still-functioning GPS to track my new exercise of choice: mountain biking (much easier on the back and far more exciting).

To Garmin's credit, the Forerunner 15 has performed admirably over the years. I've abused the thing, yet it seems to keep working day in and day out. Of course, nearly a decade of service has taken a toll on the watch aesthetically; the crystal is heavily scratched, and I've replaced the wristband numerous times. And while the internal workings seem as good as new, the rechargeable battery has expectedly degraded.

When new, the Forerunner 15 could track an hours-long run with power to spare. But around July this year, it barely lasted through a half-hour ride. I decided to try replacing the rechargeable cell myself and also wanted to polish the badly scratched crystal. Garmin, of course, does not endorse this; they state the battery is not consumer replaceable and that attempting any repairs will void the warranty. But did I mention this thing is eight-years-old? That warranty is long expired. And whether I heeded Garmin's warning and gave up - or destroyed it during my repair attempt - I'd have to buy a new one. So if there ever was an opportunity for a DIY repair, this was it.

Warnings be damned - I decided to exercise my Right to Repair.

“Right to Repair” is a DIY movement where consumers lobby for greater accessibility to the parts, tools, and information required to fix our stuff. Many products today, especially electronics (like my aforementioned GPS watch but also smartphones and the like), are engineered not to be repaired by the end user. That's right - they're made using difficult assemblies, unavailable components, unobtainable tools, and even warranty-voiding disclaimers conceived to thwart the would-be home repair person. Why? Because it's big bucks for manufacturers - they make money when we buy new, not repair the old.

As insidious as this is, corporate profits are only part of the problem.

The environmental toll from buying new products is staggering. Smartphone manufacturing alone generates more greenhouse gasses than any other consumer electronics device (reference here). Despite this, companies like Apple and Samsung churn out shiny new versions almost yearly, enticing consumers with seemingly can't-live-without features and designs. And what they build is anything but repairable. Screens are glued in, internal parts held together with proprietary screws; these devices are made to keep you out and keep the manufacturers in [your wallent].

If you can keep your phone and other consumer products going, the environmental and economic benefits are substantial. Simply delaying an upgrade by a few product cycles can have profound implications for the planet's long-term sustainability, including less extraction of raw materials, fewer greenhouse gas emissions overall, and decreased production and shipping costs. Plus, products made today take a toll on the people who make them; low-wage jobs in poor conditions continue to be the norm for many, if not most, electronics manufacturing.

The less we buy, the less of this bad stuff happens.

But your electronics must last or be repairable to make a difference. After all, screens break, batteries die, and chips malfunction. Faced with such technical hurdles and the unfortunate way these things are made, coupled with a world that now requires we have and use these things, consumers often opt to replace their failing or aging tech with new ones.

But it need not be so. [Insert the Right to Repair.]

In Right to Repair initiatives, organizations like Culture of Repair and companies like iFixIt are advocating for change and lobbying for laws that put repair rights in the hands of the consumers. And change is afoot.

Last year, Apple agreed to start supplying parts and instructions for basic repairs. And other manufacturers are adopting more consumer-focused designs that allow owners to dig in and DIY their purchases. But the transition is slow, and many legacy products we have now need repairing now, despite being designed and built for the contrary.

Like my Garmin Forerunner 15.

As mentioned, I had little to lose, so I jumped in and took my watch apart without so much as an internet search. In hindsight, I should have looked it up (see below), as everything under the sun these days has been taken apart by someone with a YouTube account. No matter, I had the tools and the will, and despite my haste, it wasn't nearly as challenging as I expected.

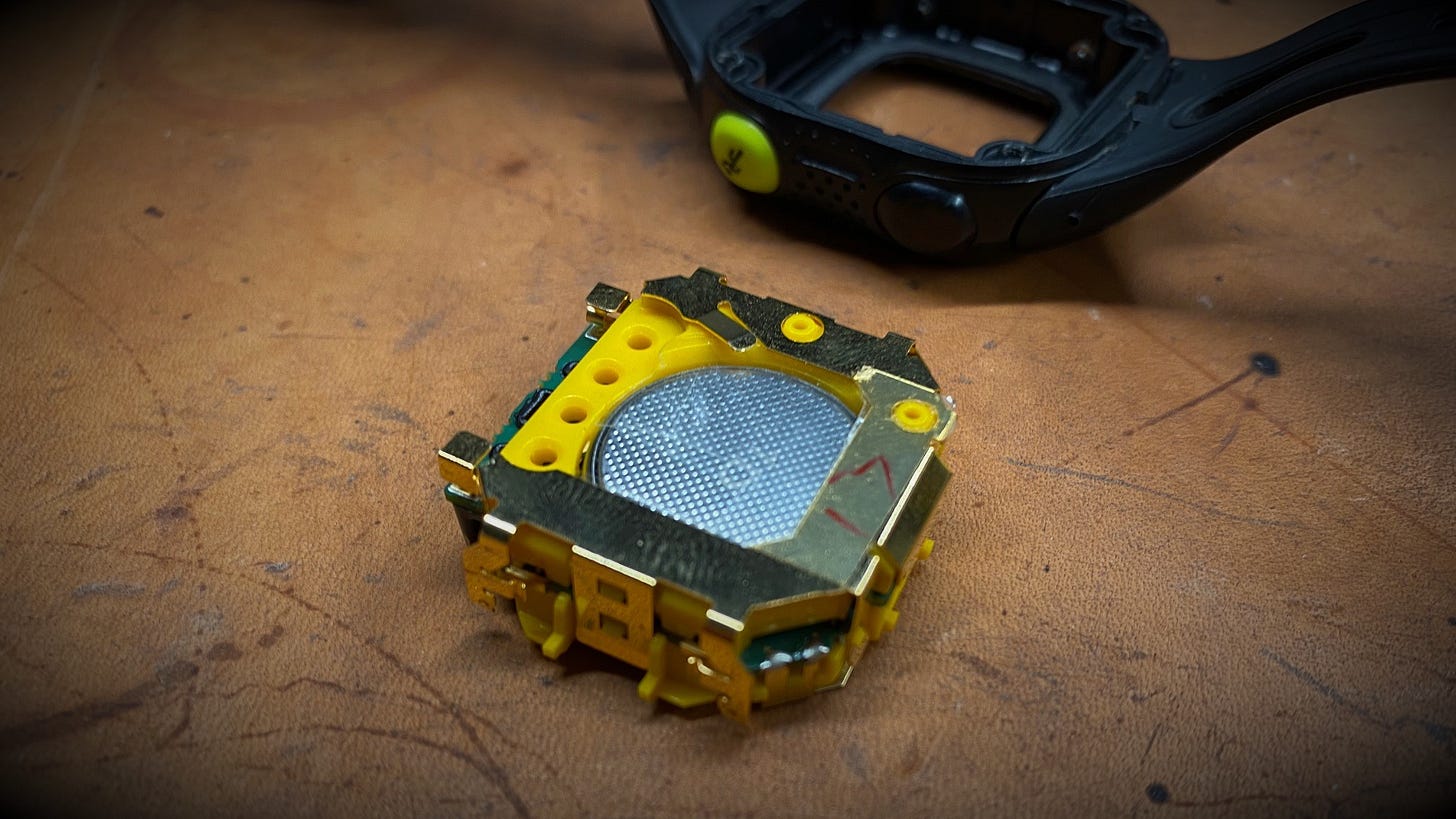

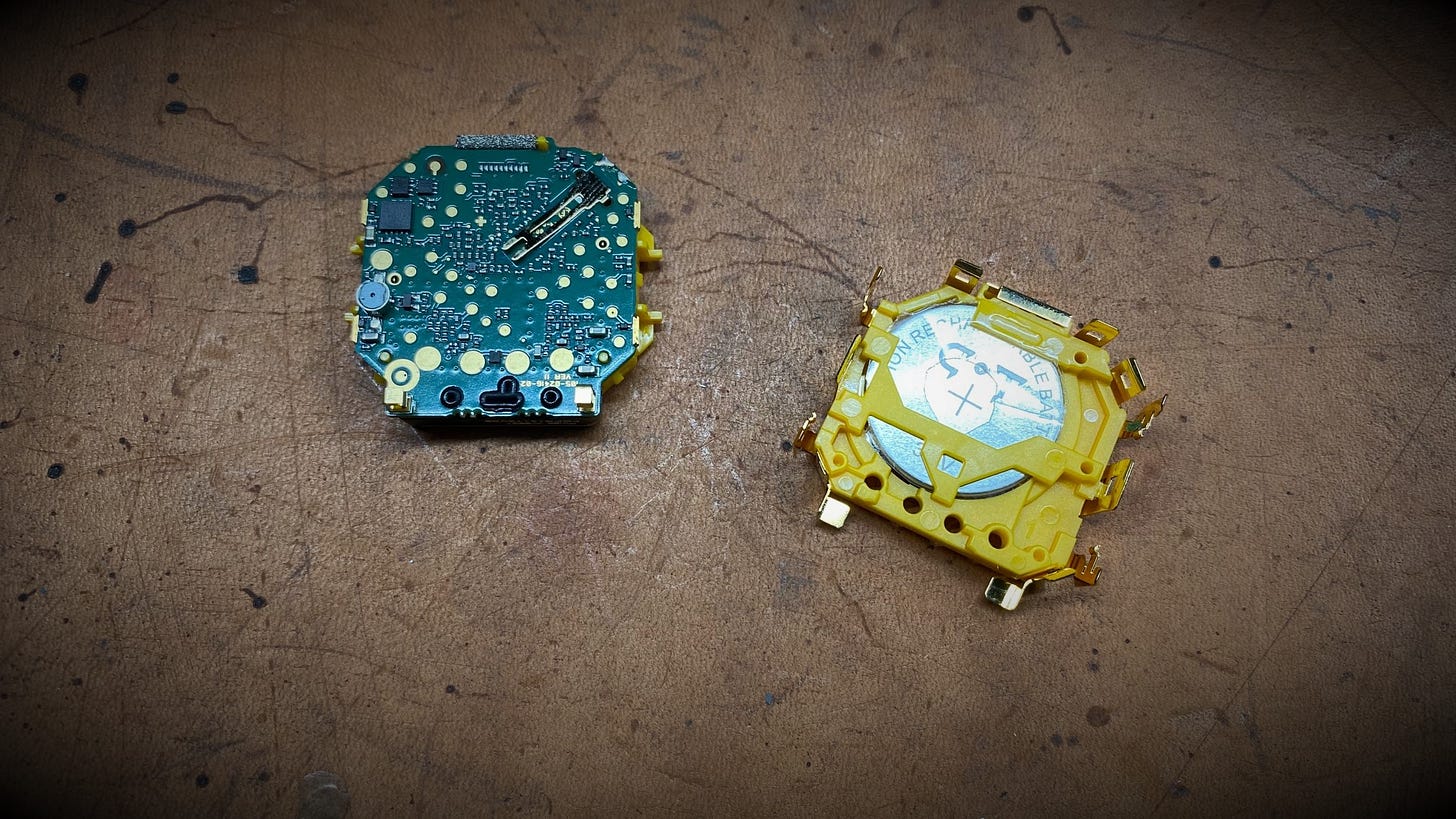

The back came off quickly by extracting the four T-5 Torx screws. Inside was a rubber ring gasket and a gold-colored metal assembly/frame that housed the main circuit board, the screen, a GPS antenna, and the battery. I instantly recognized the power cell's shape and size - it looked like a 2032 "coin style" battery (commonly used in car key fobs). I didn't know they made rechargeable versions in this size, but I was not too surprised they did.

Immediately I turned the watch over to extract the assembly, and to my shock, two infinitesimally small screws fell out. Where they came from, I had no idea. And I wasn't sure there were only two (there were, thankfully). Carefully, I collected these and placed them in a small cup for safe keeping, likewise with the screws. (Yeah, I should have looked it up first.)

Anyway, the metal housing had a few clips that kept it all together, and with a pair of tiny forceps, I detached these.

The battery was not soldered or glued in; instead, it was clipped in place by the housing and covered with transparent adhesive tape. I suspected the tape was to show evidence of tampering and was otherwise non-functional, so I cut through it to extract the battery. After finally getting it all apart, it was only then that I realized the tape did serve an essential function in the design.

The tape was an insulative barrier between the battery contacts and that gold metal housing. The whole assembly would short out without the tape strategically cut to allow connection in only two spots.

Tricky build, Garmin. But I see through your thinly disguised "repair me at your own peril" design. I could easily replace the tape with more tape, so I moved on.

After a quick search on Amazon, I found Li-ion 2032 rechargeable cells, so I ordered one, and it arrived two days later.

Installing the battery was as easy as removing it. As for the tape, I cut some clear packing tape and applied it with the needed openings for contact. And those two tiny springs? I did look it up online and determined they went in two corresponding holes in the assembly frame. (The springs appear to be additional power contacts of some sort.) I reversed the disassembly procedure and reassembled the watch - but not before a thorough cleaning and experimental crystal refurbishing.

While I had the watch apart, I decided to wet sand the crystal using successively finer-grade sandpaper. I started with 2000 grit and moved up from there, using next 5000, then 8000, 10,000, and finally 12,000 grit. Even after all of that, the glass was still visibly scuffed, so I finished with some rubbing compound and a buffing disk on my Dremel. It worked!

A few deep scuffs were still slightly visible, but the result was terrific overall.

I then cleaned it all up and put it back together.

The Garmin worked as it should, except the power indicator remained one bar below full after charging it. I suspected this was because I inserted a partially drained cell, and upon reset, this somehow was misinterpreted by the watch's software. (Pure speculation, but it was a theory I could test). So I disassembled the watch again, took out the cell, and rigged up a makeshift 2032 charger adapter for my Li-ion 18650 battery charger.

These batteries - 18650s and 2032s - are the same voltage and type (Li-ion), only different sizes, so I suspected this would work. (Note: with all Li-ion batteries, there's a fire risk, so I did this carefully and did not leave the charging battery unattended, just in case.)

The rig worked, and the battery was fully charged, with the charger's indicator light turning green upon completion. Now with the 2032 cell ready to go, I reassembled the watch for the second time, and voila! A wholly charged and functional Garmin Forerunner 15.

As with any repair, I now have a new appreciation for my GPS watch and enjoy it even more. Sure, it's woefully dated. And despite cleaning and polishing, it still looks somewhat dorky. And old. But I'm dorky and old(ish), so that's fine.

The best part of it all is the satisfaction. Fixing something Big Tech said I wasn't allowed to fix also makes me feel empowered. By repairing my GPS watch instead of buying a flashy new one, I did a small net positive for the world. That's the beauty of Right to Repair. We assume control over our stuff and reserve the right to do right by it and the planet.

I'm glad I exercised my Right [to Repair].

Until next time.

JRC

Great article of triumph over the “system”. I’m a strong advocate of the Right to Repair movement for all its environmental as well as personal emotional values. :-)