A maker fail for the win?

Losses help us explore new possibilities

I remember as a kid wanting to make so many things but not knowing how. There was this whole world of created stuff, from go-carts to rockets, that I wanted to build. Granted, I was like seven years old at the time, but still.

Back then, I always saw my dad making and fixing lots of things - he built our house from the ground up and could repair our tractor and truck, for example. And mom was similarly handy. In watching the two, I became convinced that things would work out if I put a hand to it.

Not so, of course, but this didn't deter me.

I attempted many outlandish designs throughout childhood, including the aforementioned go-carts and rockets. So too with satellite antennas, DIY parachutes, and robots of various kinds. Most of these efforts went unrewarded, but that didn't keep me from trying, time after time.

As I matured, I recognized better my limits but kept trying. And in doing so, those limits became fewer and fewer. I’d fail and try again, all the while learning how to make better and smarter. And the tools and techniques at my disposal multiplied as I learned, commensurate with this experience.

Every so often I found myself in a comfortable plateau of making, building model rocket kits, and using off-the-shelf engines to lift them into the air. It was rewarding, but never enough. I wanted custom; I wanted my own creations to soar to the heavens. So inevitably I would step out of my comfort zone and try something new, something unlikely to work.

The result was often not simply a loss but a complete failure. And I wasted a lot of materials along the way. These setbacks frustrated me, to be sure. But the losses were showing me how the real world worked. And they taught me a lot about what I needed to learn.

And so it goes with making beyond one's ability.

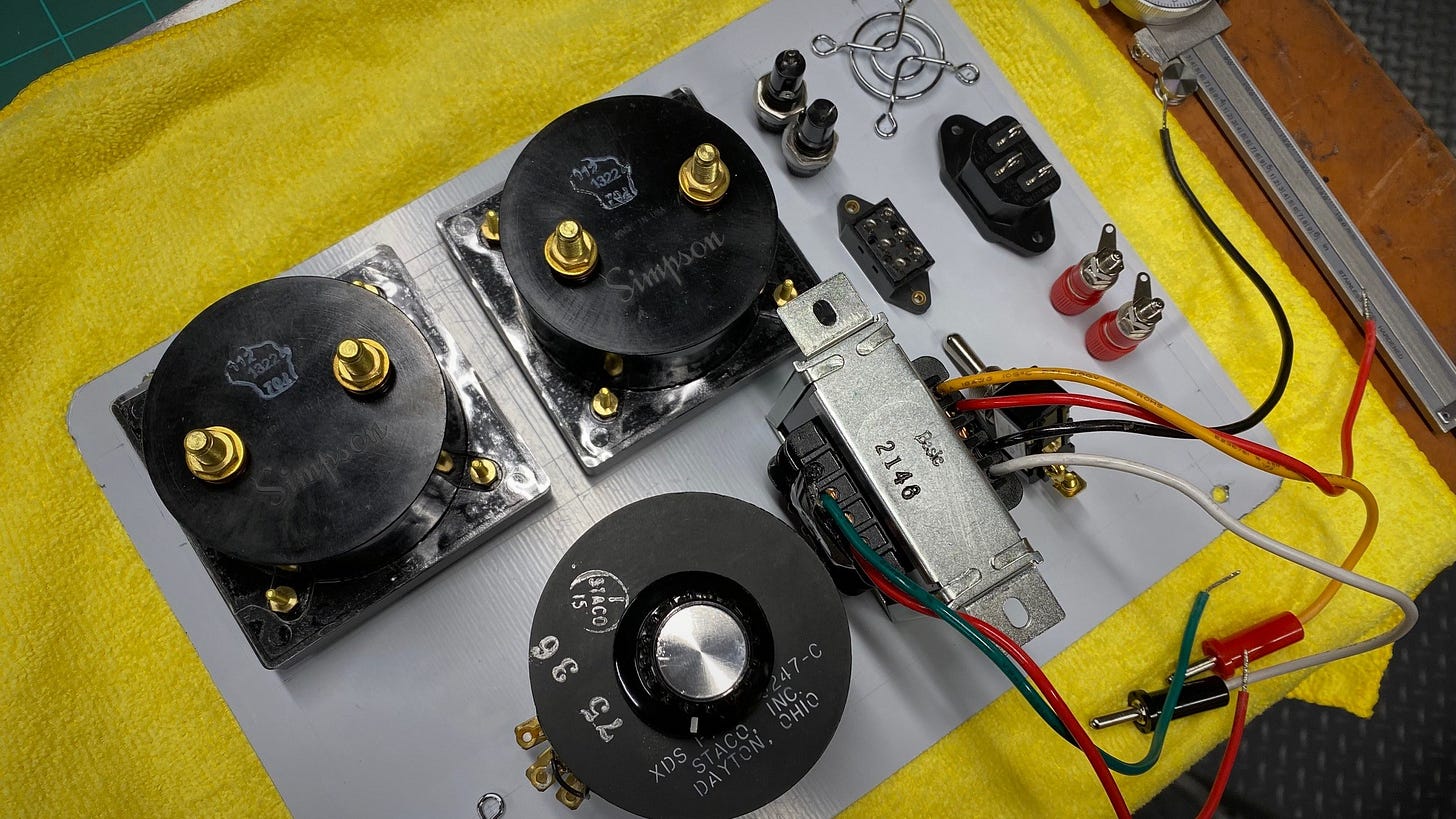

I ran into one of these personal maker limits this week as I was fabricating a project for a contract. In this build, a low-voltage AC power supply, I needed to make a control panel for all the meters, dials, switches, indicator lights, fans, and...well, everything, basically.

Anyway, all that stuff weighs quite a bit, so I opted to make the plate from aluminum for strength. But there was a sizable challenge: the parts list included two meters, each requiring a precision-drilled hole 2.75 inches (70 mm) in diameter. Now, these could easily be cut using a milling or CNC machine, but I don't have easy access to either. So I wanted to devise a solution using the tools and knowledge at my immediate disposal.

And I was coming up short.

I considered several sub-optimal options like cutting the holes freehand with a rotary tool (Dremel), cutting it on the jig saw, also freehand, or using an appropriately sized hole saw. The Dremel option would be too imprecise, so I ruled it out wholesale. I kept the jig saw option open, but I wasn’t excited about the idea - I wanted perfectly round holes. As for the hole saw, I knew it would leave a jagged edge and, worse, potentially wander away from the center. But I didn't like my other options, so I wanted to see just how bad the hole saw would be.

I gave it a go on a piece of scrap aluminum and it turned out not as bad as I feared. While its edge was slightly jagged, I could have cleaned it up with a file. But all the chips of aluminum scaped across the surface while drilling, leaving nasty scratches. This undoubtedly was a fail.

Not knowing how to proceed, I went to bed, mulling over other possibilities.

Later that night, in a semi-lucid dreamy state, it occurred to me that cutting the holes using my router would make excellent clean cuts. I only needed to find a way to control it precisely by hand.

What I needed was a jig.

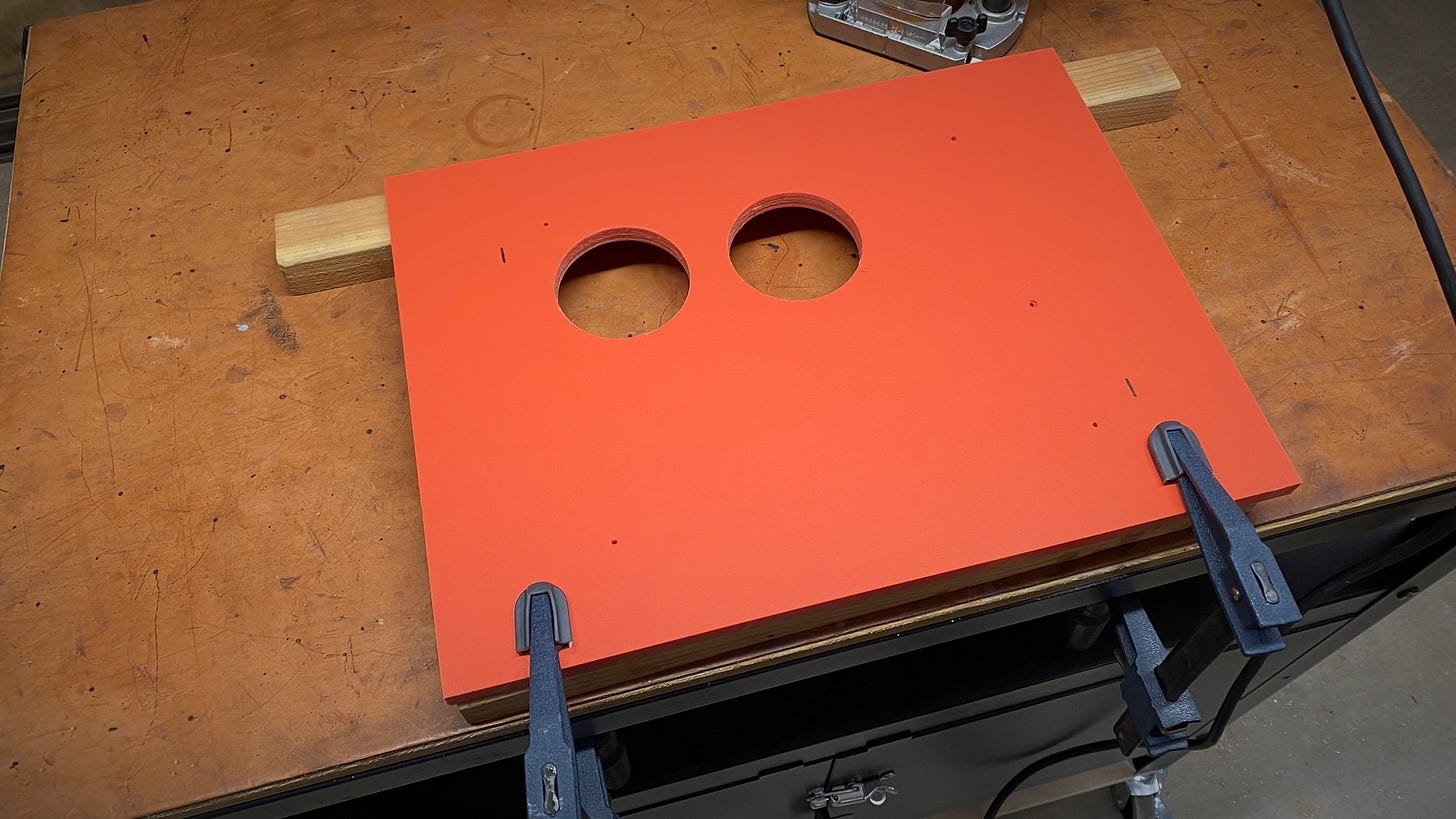

A jig is an often homemade tool used to control another tool better. I've made several over the years to do things like, for example, making cross-cuts on my table saw. Anyway, the next day I laid out my dreamed-up hole jig on an HDPE plastic sheet. With the hole saw it was a simple matter to cut two perfect holes in the sheet, these corresponding with where they'd go in the aluminum plate. (The hole saw works well in thick, softer materials like plastic and wood - not so well in thin aluminum.)

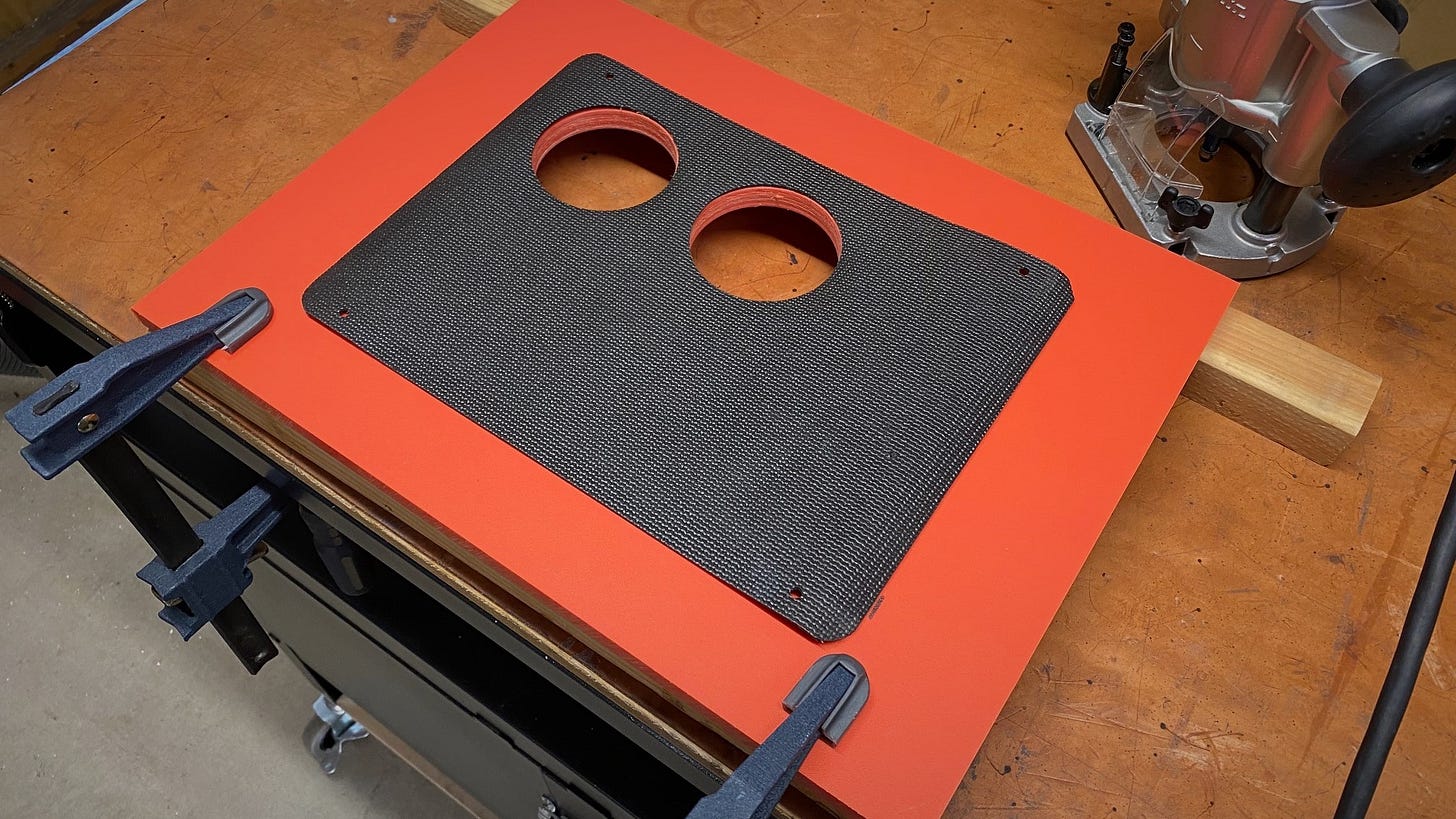

Next, I fashioned a protective sheet from rubber drawer liner to prevent scratches on the aluminum.

Finally, I fastened down the plate on the jig, and then it was simple to trace the jig with the router, cutting identical holes in the aluminum.

It worked so well that I repeated the process for two other large-ish holes I also needed (I was going to use a step drill bit for these, but the jig method worked even better). And after drilling several standard holes and making a few cutouts, the mounting plate was ready.

In retrospect, the jig method is rather intuitive. CNC machines are effectively computer-controlled routers that allow for precision execution of the router bit over intricate cuts. I had the router but needed a way to control it similarly, sans computer. The jig method did just that - on the cheap.

Sure, my hole jig is a one-off thing designed expressly for this project, and I'll have to make a different jig for any similar applications in the future. But still, it worked so well that it opened my eyes to a new set of possibilities. I didn't wholly reinvent or expand my skills but I achieved something I couldn't before.

Would I have come up with this solution without failing to do it another way?

Well, if some other method worked well enough, I might have accepted a mediocre result and moved on. But since the hole saw was a full-stop fail, I had to come up with something else. And doing something, even something that didn't work - like trying out the hole saw on the aluminum - sent me into a hyper level of obsession trying to figure out a solution (yes, I fail a lot, but that doesn't mean I like it). Anyway, all this trial and error and subsequent stewing led me to a great solution - the jig method.

Yes, I would say failure played a big part in this ultimate win.

That's the intriguing nature of "the fail." It may not be apparent at the time, and positive results down the line are never guaranteed, but thwarted attempts are learning moments, nonetheless. And if we're in tune with these events, taking from them not only what not to do but opening our eyes to see what else is possible, we steadily grow. And that growth results in achievable outcomes more often than we realize. Yes, fail for the win. It's not as conflicted as it sounds.

Until next time.

JRC

Great case study! Two things come to mind: a maxim often used in the tech industry to encourage risk taking and to discourage fear of failure, and a quote from Thomas Edison when he was asked about his many failures while trying to invent the lightbulb…

Maxim: “If you don’t fail now and then, you’re not trying hard enough.”

Edison: "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work."